Tuberculous Otitis Media with Facial Paralysis Combined with Labyrinthitis

Article information

Abstract

Tuberculosis otitis media is a very rare cause of otorrhea, so that it is infrequently considered in differential diagnosis because clinical symptoms are nonspecific, and standard microbiological and histological tests for tuberculosis often give false-negative results. We present a rare case presenting as a rapidly progressive facial paralysis with severe dizziness and hearing loss on the ipsilateral side that was managed with facial nerve decompression and anti-tuberculosis therapy. The objective of this article is to create an awareness of ear tuberculosis, and to consider tuberculosis in the differential diagnosis of chronic otitis media with complications.

Introduction

Tuberculous otitis media (TOM) can be difficult to diagnose because of its rarity, variable signs and symptoms, and non-specific manifestations compared to other types of chronic otitis media (COM). In the literature, the incidence of TOM ranges from 0.05 to 0.9% of all cases of chronic otitis media.1,2) Delayed diagnosis leads to delayed initial treatment and increased risk of serious complications, such as facial paralysis, meningitis, or irreversible hearing loss. We report an unusual case presenting as a rapidly progressive facial paralysis with severe dizziness and hearing loss on the ipsilateral side that was managed with facial nerve decompression and anti-tuberculosis therapy.

Case Report

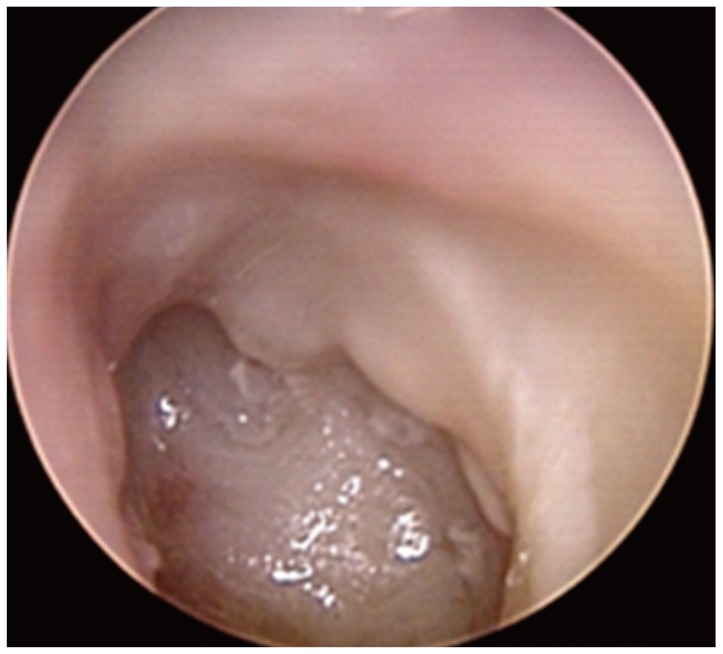

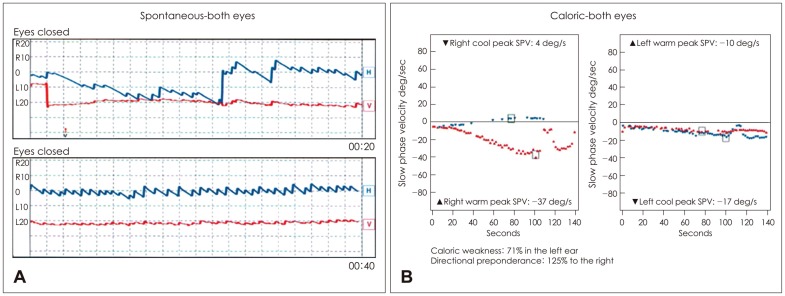

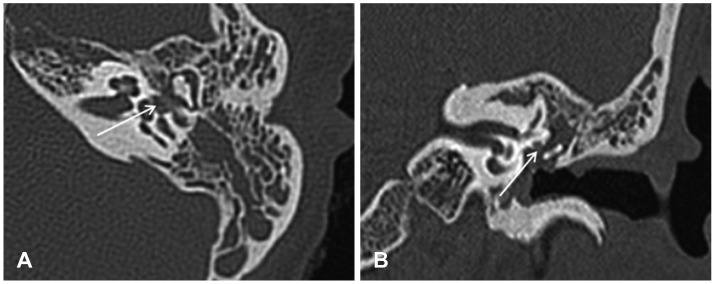

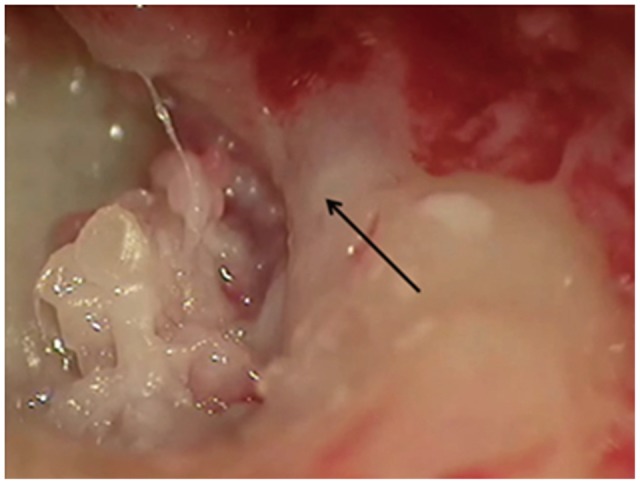

A 44-year-old woman visited our department for evaluation of progressive left facial paralysis, dizziness, and hearing loss for 7 days with a 3-month history of an intermittent discharge from the left ear. On physical examination, facial paralysis was identified as Grade V using the House-Brackmann grading system. Endoscopic exam revealed total perforation of the tympanic membrane, edema of the middle ear mucosa, and profound discharge from her left ear (Fig. 1). Initial ear culture studies did not identified pathogens. On electronystagmography, spontaneous nystagmus toward the right side was identified and left-sided caloric weakness of 71% was found (Fig. 2). She denied a history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or pulmonary tuberculosis. Pure-tone audiometry showed deafness of the left ear. A temporal bone CT scan revealed that a soft tissue density filling the middle ear cavity and mastoid, and dehiscence of the tympanic segment of the facial nerve was suspected (Fig. 3). She was initially treated with an intravenous 3rd generation cephalosporin and a 4 day course of oral prednisone (60 mg/d) was started on the day of presentation and tapered off between days 10 and 12. Preoperative eletroneurography demonstrated 75% degeneration of the facial nerve. An emergent surgical procedure was scheduled to improve facial nerve paralysis and resolve dizziness. Under general anesthesia, retroauricular incision was performed. We removed a significant amount of granulation tissue with the consistency of cheese from the middle ear and mastoid by canal wall down mastoidectomy. During the operation, dehiscence of the facial fallopian canal and a swollen facial nerve were identified and facial nerve decompression was performed to resolve the facial nerve paralysis (Fig. 4). Intraoperative finding, all ossicles were surrounded by granulation tissues and incus was partially eroded. After malleus and incus were removed, tympanoplasty was performed using temporalis fascia. The most prominent finding on histopathologic examination was chronic caseating granulomatous inflammation and many bacilli were identified on AFB stain (Fig. 5). The chest X-ray was normal, but polymerase chain reaction testing for middle ear mucosa was positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The patient was started on a 12-month course of empirical four-drug anti-tuberculosis treatment with oral rifampin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide. The post-operative course was unremarkable and dizziness resolved by post-op day 7. The patient was discharged by post-op day 14. Nystagmus was un-remarkable on electronystagmography at a 3 month follow-up visit. The facial paralysis slowly improved until it had com-pletely resolved by 4 months post-op. However, there was no change in hearing threshold by 6 months post-op.

Endoscopic findings. Total perforation of the tympanic membrane, edematous mucosa, and profound discharge documented on endoscopic exam of the left ear.

Spontaneous nystagmus toward the right side (A) and left-sided caloric weakness of 71% (B) was identified on electronystagmography. SPV: slow phase velocity.

Temporal bone CT scan (A: axial view, B: coronal view). The soft tissue density in the middle ear cavity and mastoid is shown; however, bony erosion in the temporal bone is unremarkable. Dehiscence of the ty-mpanic segment of the facial nerve is suspected on CT scanning (white arrow).

Operative findings. Dehiscence of the tympanic segment of the facial nerve is identified and cheese-like granulation tissue is seen filling the middle ear and mastoid (black arrow: swollen facial nerve).

Discussion

TOM was first reported in 1853, and the organism was first identified in ear discharge in 1883.3,4) TOM is a very infrequent cause of COM, and is rarely considered in differential diagnosis.1,5) Although the pathogenesis of TOM is still controversial, three mechanisms explaining middle ear tuberculosis infection have been postulated: aspiration of mucus through the auditory tube, hematogenous transmission from other tuberculosis foci, and direct implantation through the external auditory canal with tympanic membrane perforation.2-4) Although the symp-toms of TOM have been described as painless otorrhea with multiple Tympanic membrane perforations, exuberant granulations, and severe hearing loss, definitive diagnosis of TOM has generally been difficult since these features, such as single or multiple perforations, refractory otorrhea, deafness, vertigo, bony necrosis and facial paralysis, are present to varying degrees and do not follow a characteristic pattern.2,6,7) Therefore, initial anti-tuberculosis treatment is often delayed.

Complications occur mostly when diagnosis is delayed, and include facial paralysis, labyrinthitis, meningitis, and subperiosteal abscesses, among others.8) Facial paralysis may be present in 15-40% of TOM cases, more frequently in children.3,8) TOM should be suspected when a patient with COM presents with facial nerve paralysis. After confirming the diagnosis of TOM, the treatment of choice is the standard pharmacological treatment used for other forms of tuberculosis. Antituberculosis treatment improves the prognosis for most patients.1) For complete cure, medical therapy should last for a minimum of six months and surgical treatment should be added to medical therapy in cases with complications.2)

In our case, we preoperatively diagnosed COM with facial paralysis combined with labyrinthitis based on the patient's symptoms, and treated with canal wall down mastoidectomy and facial nerve decompression. After pathologic confirmation of TOM postoperatively, antituberculosis medication was started immediately.

In conclusion, although TOM is a rare entity, otologic surgeons should be vigilant for suggestive clinical signs such as painless otorrhea, abundant granulation tissue, facial paralysis, or a family history of tuberculosis.1) Including this disease in the differential and considering it will lead to prompt treatment and prevention of serious sequelae.