Development of a School Adaptation Program for Elementary School Students with Hearing Impairment

Article information

Abstract

Background and Objectives

Although new technology of assistive listening device leads many hard of hearing children to be mainstreamed in public school programs, many clinicians and teachers still wonder whether the children are able to understand all instruction, access educational materials, and have social skills in the school. The purpose of this study is to develop a school adaptation program (SAP) for the hearing-impaired children who attend public elementary school.

Subjects and Methods

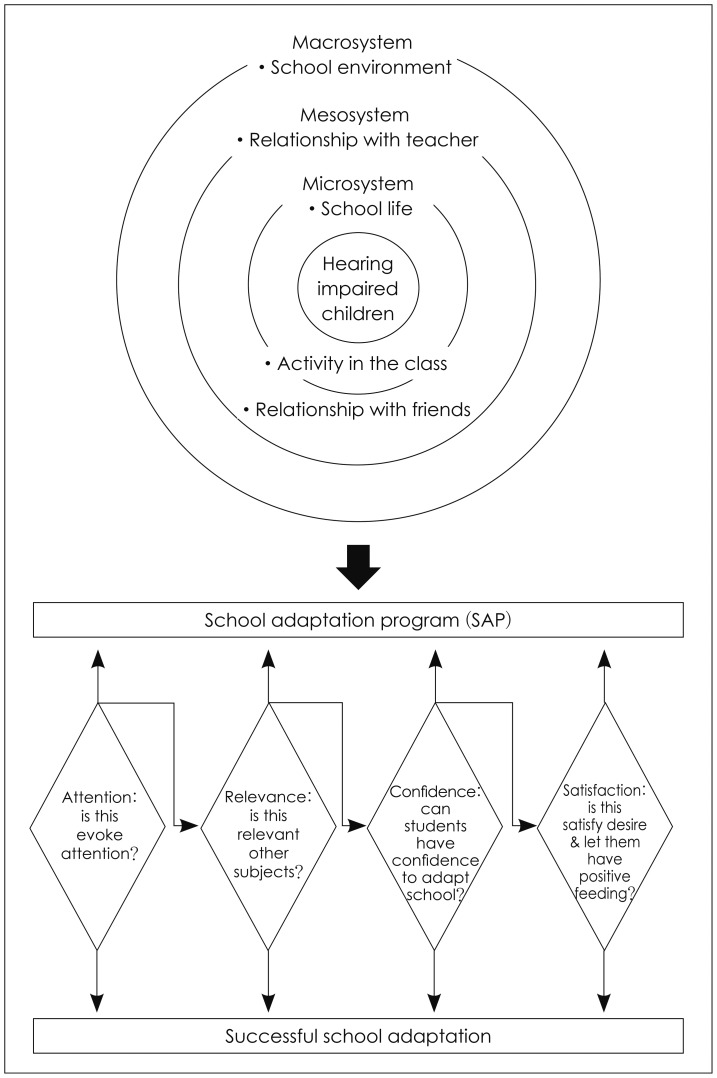

The theoretical framework of the SAP was a system model including microsystem, mesosystem, and macrosystem merged with Keller's ARCS theory.

Results

The SAP consisted of 10 sessions based on five categories (i.e., school life, activity in the class, relationship with friends, relationship with teacher, and school environments). For preliminary validity testing, the developed SAP was reviewed by sixteen elementary school teachers, using the evaluation questionnaire. The results of evaluation showed high average 3.60 (±0.52) points out of 4 while proving a reliable and valid school-based program.

Conclusions

The SAP indicated that it may serve as a practical and substantive program for hearing-impaired children in the public school in order to help them achieve better academic support and social integrations.

Introduction

In general, people are in harmony with their external relationships (i.e., family, friends, and acquaintances) while promptly responding to various and continuous stimuli from nature and social environments internally and/or externally. However, if they lack this harmony with others during the social adaptation period, they are likely to experience negative emotions such as frustration, tension, and dissatisfaction [1]. In an academic environment, adaptation occurs when people encounter ordinary school life. According to system theory, school, a kind of system, have interrelationship with the subsystem. It functions adequately when the constituent factors work including microsystem, mesosystem, and macrosystem. It is an open system and operates continuously reciprocal action mutually through input and output. Thus, positive and communicative relationships with teachers and friends are important factors in children's early school and classroom adjustment [2,3]. Ladd and Burgess [4] suggested that school adaptation indicators include support from friends, the likelihood of avoidance of school, the level of participation in class activities, and achievement related to learning. Also they reported that school adaptation could be altered by various educational settings.

The U.S. Department of Education [5] reported that approximately 89% of hearing-impaired students and over 75% of deaf or hard-of-hearing students attend public schools [6]. In Korea, approximately 69% of hearing-impaired students are also enrolled in public schools, and the number of students is increasing every year [7]. That is, the development of new medical and audiological technologies, i.e., hearing aids and cochlear implants, causes many of hearing-impaired children can attend public school instead of choosing special school. However, their adaptation to the public school is often more difficult than expected, resulting in those students ultimately returning to the special school. It is assumed that individuals with developmental disabilities are three to five times more likely to have a severe behavioral disorder or mental health problem than their typically developing counterparts, reported by epidemiological studies [8]. A child's competence is related to his or her standing in the peer group at school. In addition, externalizing problems (violations of rules and the rights of others), internalizing problems (sad mood, anxiety, and loneliness), and concentration problems (difficulties in attention and motor control) are detrimental to positive school experiences, and unfortunately can contribute to problems later on. Because of their hearing difficulties, these students face potential negative outcomes including academic problems, social-emotional problems, and behavioral and/or mental health problems, all of which are likely to be detrimental to the students' overall school experience. If maladaptive behavioral signs or problems are not diagnosed at the elementary level, the problematic behavior can continue and increase, eventually becoming a severe adaptive disorder [9]. Therefore, if one experiences adaptive difficulty during elementary school, the degree of severity should be detected as early as possible and appropriate intervention should be undertaken [10].

Successful adaptation to school is likely influenced by a number of factors including academic, social, emotional, behavioral, and cognitive competencies [11,12]. The student who adapts successfully to school life has a positive feeling, attitude, and motivation about school; therefore, his interpersonal relationships will be amicable, his academic record will improve, and his behavioral characteristics will be desirable, ultimately contributing to school and social development as well as to personal growth [1]. A supportive school program can positively alter the school environment in which hearing-impaired students enrolled in [13]. The goal of the school adaptation program (SAP) is to create a supportive system that helps the hearing-impaired children become involved in play activities in which they can get positive school experience such as cooperation, mutual understanding, and consideration from others. This may have a positive effect on the hearing-impaired student's peer relationships, improve peer attitudes about hearing-impaired classmates, and help teachers to better assist hearing-impaired children to successfully adapt to school. School experiences influence students for the rest of their lives. Therefore, a program is needed to help hearing-impaired students successfully adapt to school life. Also, it must be applicable in school fields and situations. The purpose of the present study is 1) to develop a schoolbased adaptation program for hearing-impaired children and 2) to test potential validity from school teachers who spend times with the hearing-impaired children.

Subjects and Methods

This research is a methodological and descriptive study intended to develop a SAP and preliminary validity testing through users' evaluation.

Process of SAP development

The present study focused on hearing-impaired 7-to-12-year-old elementary school students. Program content for school adaptation related to hearing-impaired children was developed based on the former researcher results regarding school adaptation [1,11] and with the deep discussions of the experts (i.e., school teachers, nursing faculties, and audiology faculty), we isolated five categories that can affect children's school adaptation: school environment, relationship with teacher, activity in the class, relationship with friends, and school life. Then, the systems that can affect a student's adaptation to school were divided into three systems: microsystem, mesosystem, and macrosystem [14]. Finally, the system was connected with a Keller's ARCS theory [15] as a teaching model (Fig. 1).

Based on an understanding of hearing-impaired children, the microsystem involves school life and activity in the class. Children begin to acquire and practice new skills and use spoken language during class. However, hearing impairment during activities associated with language and learning problems in the class may cause concentration problems and lessen the motivation to study, resulting in detriments to school life. Thus, these students may seem to be aggressive, behave egocentrically, violate school rules, and avoid school life. Mesosystem, a middle system that influences microsystem, involves relationships with teachers and friends. The adaptation of hearing-impaired children has most often been studied in terms of school achievement, social competence, and behavioral problems. This system emphasizes social skills. That is, interpersonal relationships surrounding the hearing-impaired students have a considerable influence on the adaptation to school. Macrosystem is the largest system and includes both microsystem and mesosystem. This system focuses on school environment. Because hearing-impaired students' school adaptation is associated with this problem as well as personal disability, school adaptation should be dependent on interacting with the school environment. Thus, it must be changed to support the students to adapt to school successfully.

Keller's ARCS theory is a valuable because it gives motivation to learners and consists of four sub-categories: attention, relevance, confidence, and satisfaction [15]. "Attention" suggests that the student is interested during the class. "Relevance" refers to interacting with other subjects' contents of school curriculum. If they feel that the contents of SAP do not excite students' curiosity, their motivation will disappear. "Confidence" means that hearing-impaired students succeed with SAP. "Satisfaction" is related to how satisfied students are with the SAP and whether it results in positive feelings.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the institute at which the researchers were affiliated (IRB No: HIRB-2013-027). The IRB confirmed that there were no elements that would be depriving human rights, and that all contents and process conformed to appropriate for research ethics.

Preliminary validity testing of the SAP

For preliminary validity testing, sixteen elementary school teachers working three districts from Seoul, Ilsan, and Chuncheon cities were participated. The participants were all female and the age ranged 29-42 years old who had at least five years of experience working at schools where hearingimpaired children were enrolled in. Among them, eight (50.0%) were elementary education, six (37.5%) were special education, and two (12.5%) were health education. They performed developed SAP validity testing while using the questionnaire consisted of 12 items. Each expert rated on a fourpoint Likert scale (1="strongly disagree," 2="disagree," 3="agree," and 4="strongly agree"). The higher scores indicate the more validate the SAP. Cronbach's alpha was found for the total scale as 0.884 indicating good internal consistency.

Data analysis

Data analysis performed using SPSS Win 21.0 (IBM Inc., New York, NY, USA) to describe descriptive data, including means and standard deviations.

Results

This study was conducted with a systematic approach for hearing-impaired children to adapt to school life. The program of microsystem, mesosystem, and macrosystem was divided into five categories consisting of school life, activity in the class, relationship with friends, relationship with teachers, and school environments. Each category had teaching plans for two sessions (10 total sessions) that contained teaching goals, contents, and teaching methods and requirements. Finally, the SAP was peer-reviewed by the teachers who would use it in the future.

The developed SAP

Microsystem

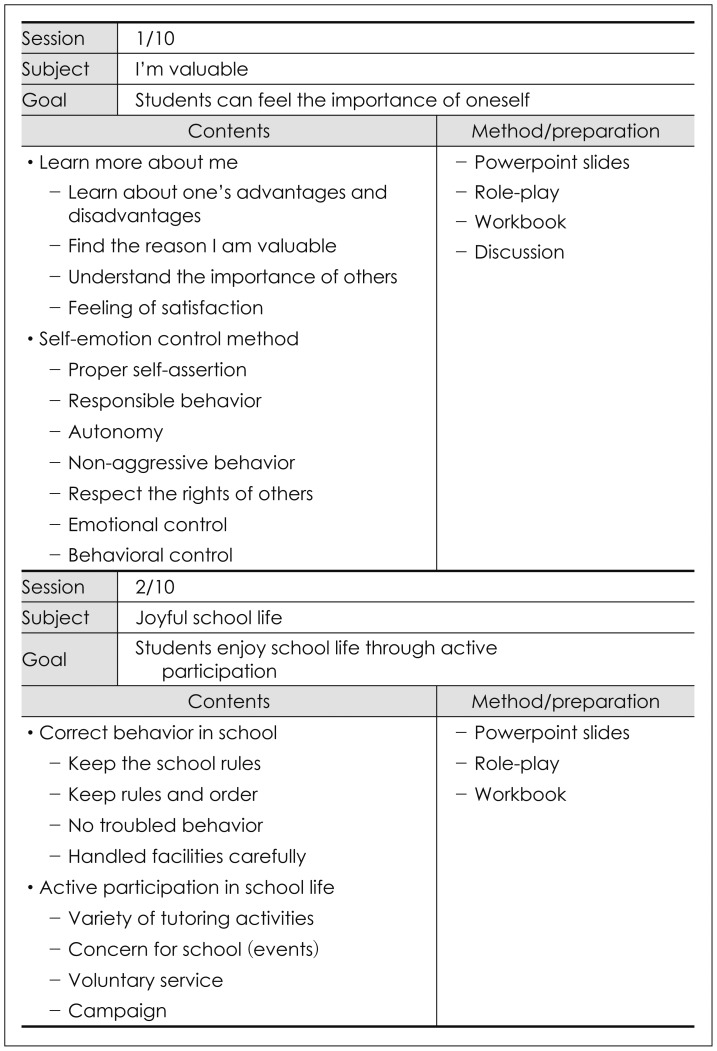

The microsystem included the categories of school life and activity in the class. The school life category consisted of two sessions of which the duration was 40 minutes per session. The first session was intended for children to realize their importance and prove themselves without losing their temper, and the second session enhanced its content more specifically for them to understand the regulations and rules of school and to actively participate in school life (Fig. 2).

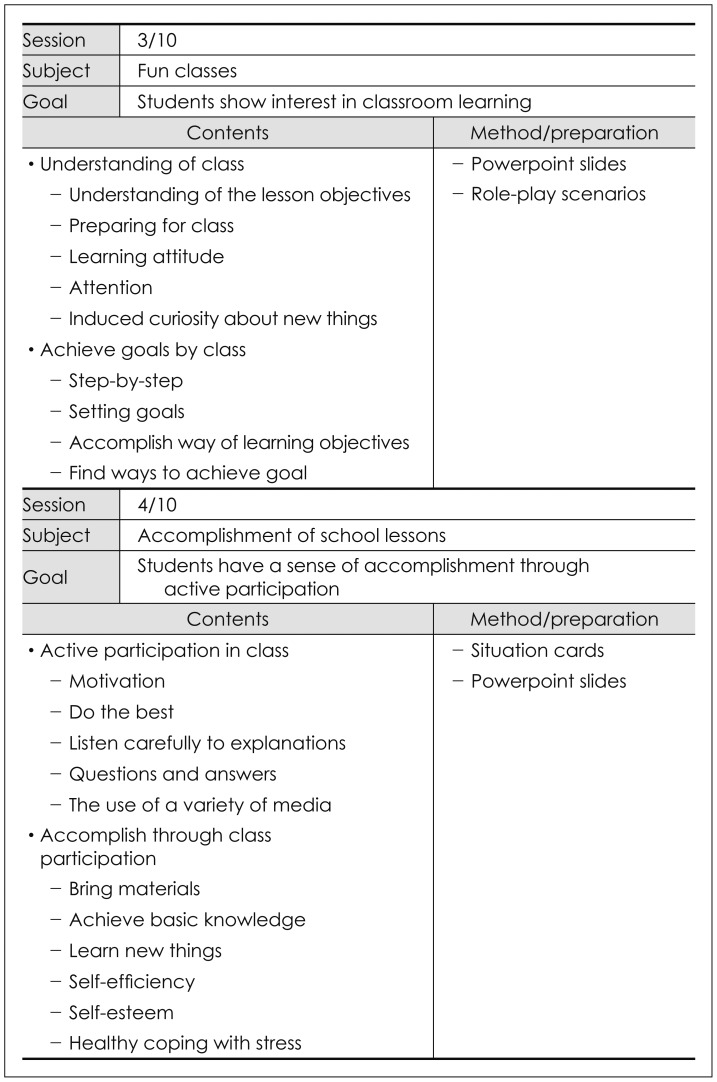

The category of activity in the class was taught in the third and fourth sessions. The third session was to understand the teaching overall and to set their own teaching goals themselves. The fourth session was for them to express their self-satisfaction by achieving their goals through utilizing various methods by participating in the class voluntarily (Fig. 3).

Mesosystem

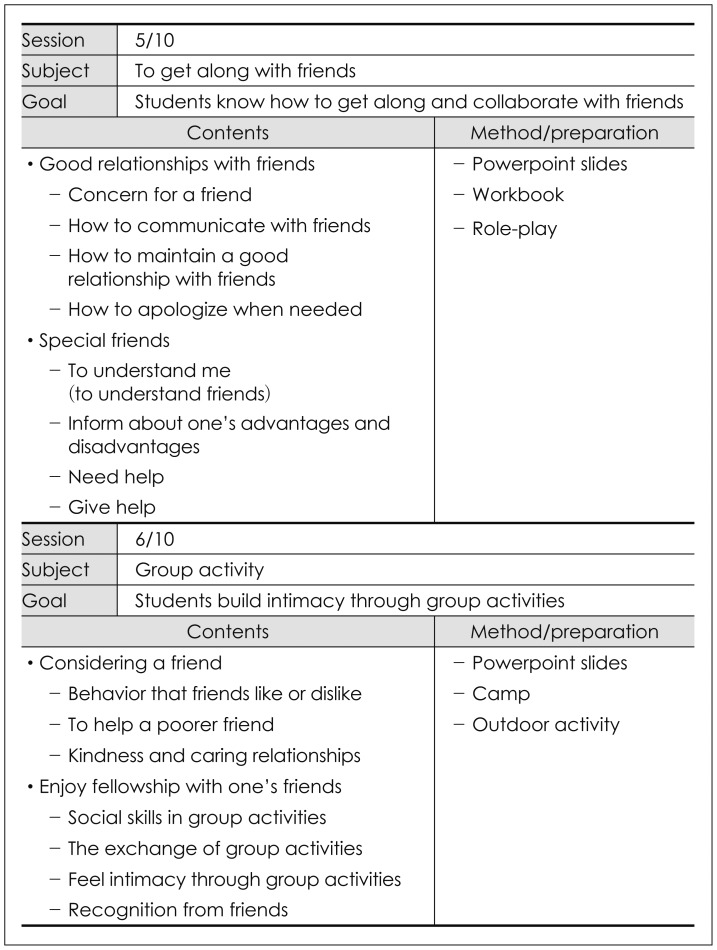

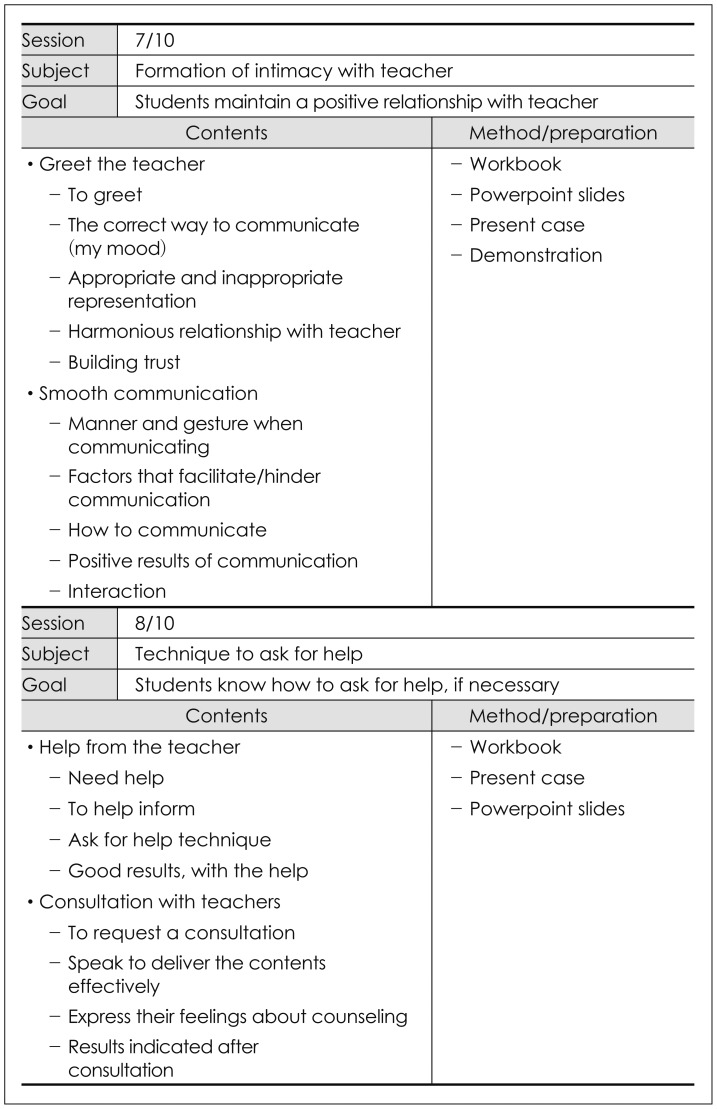

Mesosystem included the interaction among friends and teachers that could affect most mutually. The interaction among friends in the fifth and sixth sessions involved teaching the ways to get along well with friends by learning how to communicate with them and how to help each other. The sixth session also let them experience intimacy and social skills in the group activities with friends (Fig. 4). It also allowed them to communicate with teachers in a smooth way and ask for specific help or consultation (Fig. 5).

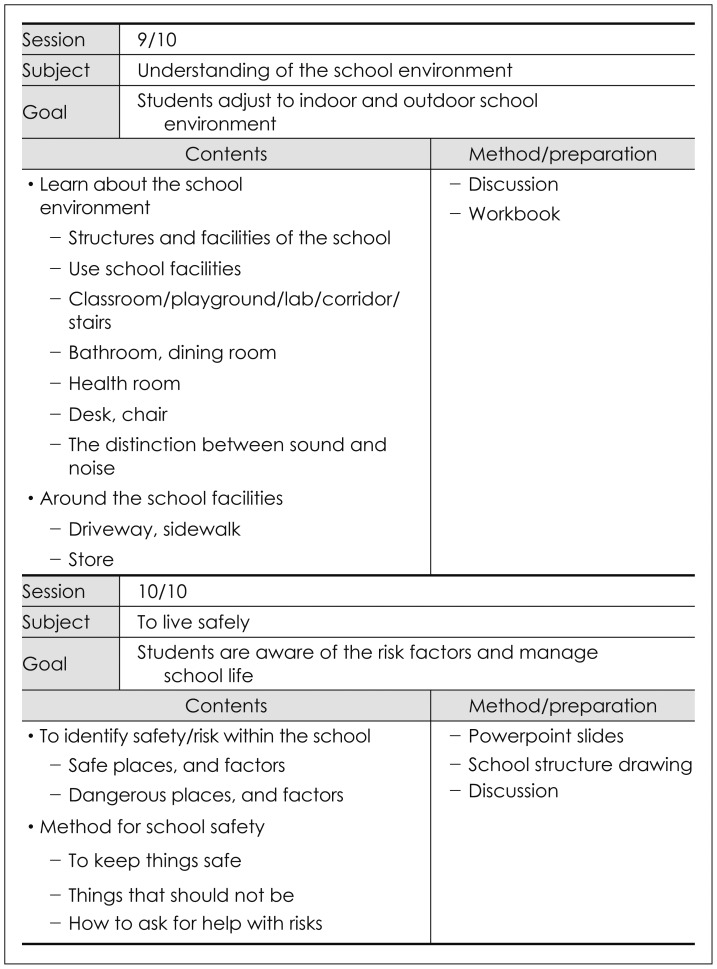

Macrosystem

Macrosystem surrounded by mesosystem included school environments. It allowed hearing impaired-children to commute school safely by observing and investigating both in and outside of school environments. It also let them learn how to ask for help when they were in danger or how to help other people who were in danger through various modes of teaching (Fig. 6).

Preliminary validity testing of the SAP

Each review item was listed based on Keller's ARSC (attention, relevance, confidence, satisfaction) [16]. The items of #1, 2, and 3 referred to attention, #4, 5, and 6 corresponded to relevance, #7, 8, and 9 regarded confidence, and #10, 11, and 12 related to satisfaction. The results showed that every item marked higher than 3.5 points on a maximum scale of 4.0 points. The mean score in each category of overall item was 3.60 (±0.52): 'attention' was 3.56 (±0.49), 'relevance' was 3.65 (±0.63), 'confidence' was 3.65 (±0.47), and 'satisfaction' was 3.52 (±0.50) (Table 1). In addition, the teachers were asked to provide detailed feedback comments freely about its contents, time, and utility in the school field. The majority of teachers said that the developed SAP was easy, applicable and useful in the school situations. Thus, the SAP considers met the needs of teachers in school. Through this process, the developed SAP was potentially validated.

Discussion

The present study was designed to develop an essential SAP to help hearing-impaired children in public schools. In this study, the SAP consisted of five categories: 1) school life, 2) activity in the class, 3) relationship with friends, 4) relationship with teacher, and 5) school environments.

Hearing-impaired children were rated as less socially competent than children with normal hearing. Moeller [16] found the deaf child to be underdeveloped in his social and emotional development. Psychosocial adjustment related to effectiveness of communication may be involved in early communication for deaf children [17]. In general, deaf children exhibited, rigidity, egocentricity, and delayed emotional maturity resulting in communication deficiencies [18]. Thus, deaf children's emotion regulation strategies appeared less effective than those of their hearing peers. Compared to their hearing peers, deaf children show a lower self-esteem, fewer psychosocial and more withdrawn behaviors, they feel less accepted and more often feel rejected and lonely [19]. Therefore, the hearing-impaired students will learn more about their value and learn how to control self-emotion through session 1 of the SAP. In session 2, students can enjoy school life through various school events as members of clubs such as sports, music, orchestra, theatre, and voluntary services. Participating in these events lets them maintain school rules and orders while limiting troubled behavior [20].

Many previous studies have pointed out the maladjustment of disabled children who attend public school [21]. For example, hearing-impaired children have difficulty in listening to the teacher's speech, resulting in poor language acquisition and comprehension compared to their friends with normal hearing (or hearing peers). They are a little slow to learn new information and have weaknesses in maintaining and generalizing it. This may give rise to serious trouble with class lessons and low performance on exams. Thus, if hearing-impaired children learn the same curriculum subjects as their hearing peers without any special care or consideration, they often feel isolated and separated from the class [8]. They usually display poor learning performance and have negative experiences in social relations with their teachers and hearing peers, which lead to low self-esteem or increased behavioral problems. Kwon [22] reported that about 80% of hearing-impaired children showed difficulty in understanding topics in class and the top 20% of the hearing-impaired children were less than 10% of the total class, which demonstrates their poor learning achievement. Mirandaa, et al. [23] reported that although 33% of hearing-impaired people were independent in learning and social adaptation, 46% of them still needed some aid. Thus, hearing-impaired children who attend public school should be considered in need of extra help. Therefore, in session 3, the hearing-impaired children will be shown how to prepare for class, pay attention, and understand the objectives of the lesson. Session 4 will let those set goals themselves step-by-step and find ways to achieve those goals.

As they get older, children form a peer group. The relationships with their friends are very important during their lifetimes [24]. That is, the relationship with friends is the first social relationship outside of the family, and it gives them criteria for self-evaluation [25]. It has been reported that peer relationships significantly influence adolescent risk behavior and that rejection by peers increases the likelihood of developing psychopathology. Since their hearing peers are often outspoken, cynical, and uninterested in disabled children or sometimes force them to do inappropriate things, hearing-impaired children often have trouble with self-worth and selfawareness in front of their hearing peers. Kent [26] reported that individuals with disabilities often experience a sense of shame and attempt to disown the parts of the self that reflect the prevalence of negative stigma. Highly related to poor peer relationships, children with poor adjustment were also at risk for difficulties in later life. Therefore, hearing-impaired children should learn to form good relationships with friends and make special friends through session 5. In session 6, they will develop intimacy through group activities.

In addition, the student-teacher relationship is very important for children's adapting to school [27]. Since the class teacher is one of the key factors of the classroom adaptation and spends the most time with the children during the school day, he or she has a significant effect on the children [25]. In other words, the class teacher who engages with the children all day long is the best person to identify a struggling child in the school system [11]. Much literature supports that as children perceive a positive relationship with their teacher or are supported by the teacher, they are well adapted to school life [25]. That is, the relationship with the teacher was related to the class and school adaptation. Kim's study [28] of school adaptation revealed that gaining the recognition of the teacher is the most important factor. Park, et al. [29] determined that a teacher's personality and relationship skills would directly affect development and school adaptation of elementary students. Some children with a lack of attention during class attract the negative notice of the teacher or bother other students, whereas the children having a positive relationship with the teacher or good friendship with classmates are well adapted to the school [30]. In conclusion, the hearing-impaired children will be able to maintain a positive relationship with the teacher while learning how to greet the teacher and use appropriate manners and gestures when communicating in session 7. After completing session 8, they will know how to ask the teacher for help.

The SAP for children with hearing impairment should also consider school environments (indoor and outdoor) as one of the most important factors. It is for this reason that the adaptation of children with disabilities who attend public school is able to include unexpected issues caused by school environments as well as limitations of the students' abilities due to disabilities. Therefore, hearing-impaired children should learn about the school environments, including structures and facilities of the school (i.e., classroom, laboratory room, restroom, cafeteria), and around the school facilities (i.e., driveway, sidewalk) (session 9). They also learn to be aware of the risk factors around them and how to live safely while differentiating safe places from dangerous places and factors in session 10, while also learning to ask for help when they encounter a risk.

In this study, we developed the SAP and preliminary validity testing. If there is any category of maladaptation of school life, the experts including school teachers and audiologists observe and help them to cope with the problems. With the aids of the experts for hearing-impaired children, it could improve the function of hearing, and finally, lead them to adapt school successfully. If they complete elementary school, their positive experience often follows to junior and senior high schools. Supporting students helps not only the adaptation and development of individuals but also enhances the efficacy of school administration. With the cooperation of the school teachers, the audiologists can play an important role in integrating the hearing-impaired children into the public school.

Limitations of the study

This study had some limitations. First, the SAP was developed by the researchers and used preliminary validity testing. Thus it should be retested for its reliability and validity through continuous studies by a large size of hearing-impaired children. Second, the present study, it does not measure the effects of SAP. In the further study the effects will be estimated, through the application of SAP.

Recommendations for further research

Almost 3.65 million citizens in the United States and the European Union are born with or acquire (before the age of 18) a hearing impairment that is severe enough to affect their educational opportunities. Individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing struggle with personal and social identity because they have to "acculturate to the hearing world" [31]. Identity development is often more difficult for adolescents who are deaf and hard of hearing because of the impact of hearing loss on communication, interpersonal relationships, and education [32]. In other words, various programs will be developed and applied for hearing-impaired children who want to adapt to public school at the level of elementary school.

The SAP developed by the present study might provide appropriate school-based intervention to children's maladaptive behavior and poor social skills while enhancing self-esteem, correcting undesirable behavior, making school life a joy through active participation, developing good relationships with friends and teachers, and adjusting to school environments. In the future, we can see the effects of the developed SAP in a larger sample size of children with hearing loss in the adaptation to school in order to expand our knowledge on the effect of hearing loss on children's emotional understanding and functioning.

Conclusion

Hearing-impaired children may be at risk for non-optimal development in terms of adaptation in school. The SAP for hearing-impaired children was developed and preliminary validated. It consisted of a microsystem, mesosystem, and macrosystem including five categories, merged with Keller's ARCS (attention, relevance, confidence, and satisfaction) model. The SAP was estimated by future users, elementary school teachers, as a reliable and valid school-based program. This may ultimately accomplish successful school adaptation. This study also advances the blueprint of school adaptation not only for hearing-impaired children but also for disabled children in various school settings. Furthermore, it suggests that full integration of the SAP into the curriculum will be needed.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant, funded by the Korean Government (NRF-2012S1A 3A2033480).