Sixth Cranial Nerve Palsy and Vertigo Caused by Vertebrobasilar Insufficiency

Article information

Abstract

A 38-year-old woman presented with a week’s history of binocular horizontal double vision and acute vertigo with gaze-induced nystagmus. We considered a diagnosis of one of the six syndromes of the sixth cranial nerve and evaluated several causes. She had history of severe anemia, vitamin B12 deficiency, and hypertension. Magnetic resonance imaging with angiography showed stenosis of the right vertebral artery and hyperintensity on both basal ganglia. As we describe here, we should consider vertebrobasilar insufficiency as a cause for sixth cranial nerve palsy if a patient has high risk for microvascular ischemia, even in the absence of acute brain hemorrhage or infarction.

Introduction

An affected sixth cranial nerve is the most frequent cause of an isolated ocular motor palsy, which typically presents as horizontal diplopia that worsens on ipsilateral gaze, especially when viewing something at a distance [1]. Sixth cranial nerve palsy is often a benign condition with full recovery within weeks, yet caution is warranted as it may portend a serious neurologic process. There are various causes for sixth cranial nerve palsy including stroke, infection, Lyme disease, brain tumor, meningitis, diabetic neuropathy, multiple sclerosis, and brain aneurysm [2]. Ischemic monomelic neuropathy (IMN) is well known as the most common cause of an isolated sixth cranial nerve palsy [3]. It is an infrequent problem that usually occurs after acute arterial occlusion or low blood flow due to hemodynamic alterations including venous hypertension, arterial steal syndrome, and high-output cardiac failure.

A small spontaneous hemorrhage of the right pontine tegmentum induces vestibular syndrome, a conjugate gaze paralysis toward the right side, and transient right facial palsy [4]. Because the sixth cranial nerve has the longest subarachnoid course among all cranial nerves, it is imperative to analyze the relevant clinical signs and the many possible etiologies through involvement of contiguous structures. Computed tomography (CT) scans or Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may reveal more detailed information on the sixth cranial nerve’s entire course [5]. Axial T1-weighted images, before and after IV administration of contrast material, are helpful in evaluating the course of the cisternal and petrous portions of the sixth cranial nerve. Here, we describe a case of unilateral sixth cranial nerve paralysis with central vertigo and gaze-induced nystagmus due to vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI), and in which symptoms resolved after treatment within a week.

Case Report

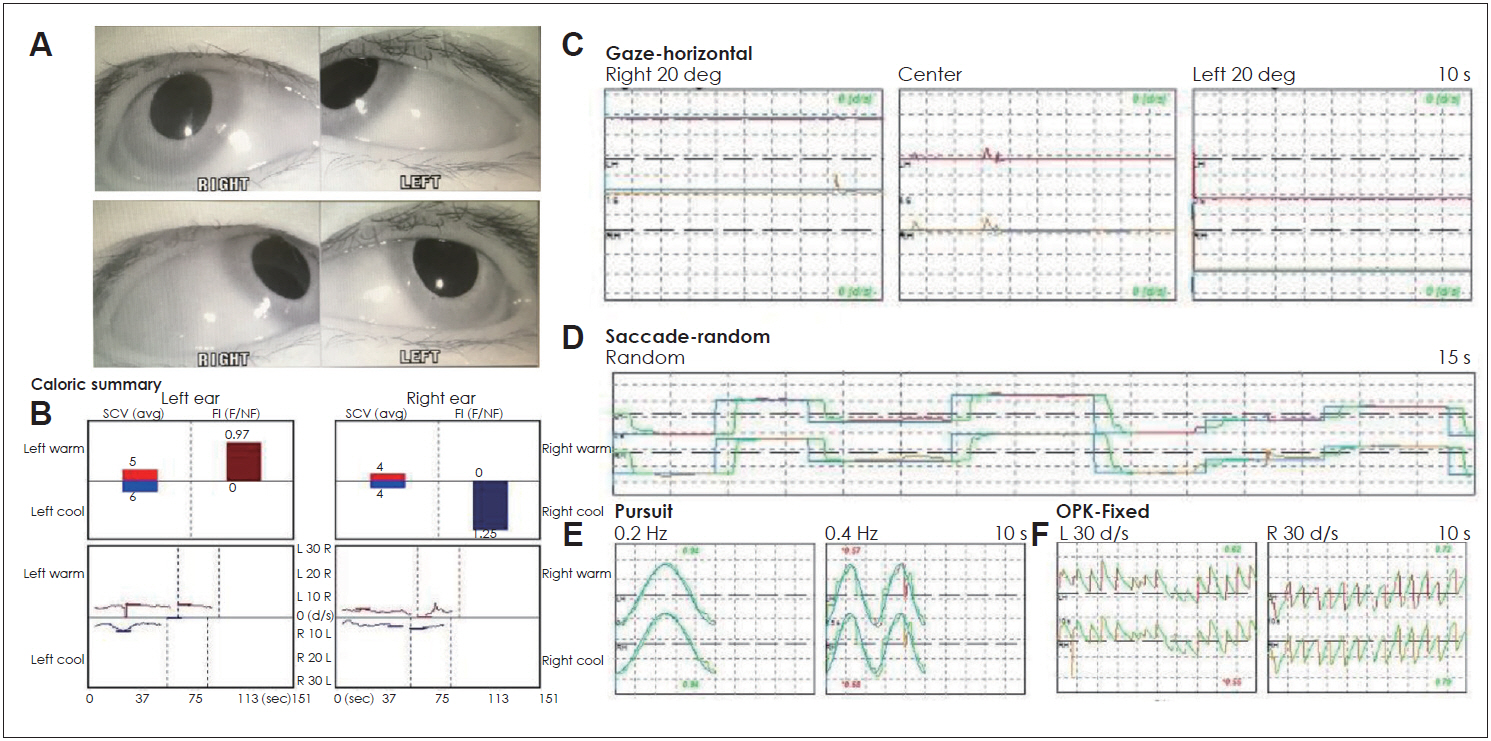

A 38-year-old woman presented with a week’s history of binocular horizontal double vision and acute vertigo with vomiting in an emergency room. She had hypertension and iron deficiency anemia with a history of transfusion for 6 months. The vertigo with a spining sensation began intermittently 6 months prior, and in this instance, started 2 weeks prior presentation. Physical examination revealed a complete paralysis of abduction of the right eye resulting in a paralysis of conjugate gaze towards the right side (Fig. 1, Supplementary Video 1 in the online-only Data Supplement). There was no strabismus and both eyes were in the midline at rest. Vertical eye movements (saccades and pursuit) and convergence were normal. Gaze-induced nystagmus (right beating when looking to the right side and left beating when looking to the left side) was observed with up-beating spontaneous nystagmus. Dix-hall test and head rolling test showed no change in nystagmus. There was no dysmetria in the finger-to-nose test. There was neither pupillary abnormality nor cranial nerve deficit. CT scan and brain MRI revealed neither acute brain hemorrhage nor recent infarction. She was admitted to the neurology department under the suspicion of one of the six syndromes of the sixth cranial nerve.

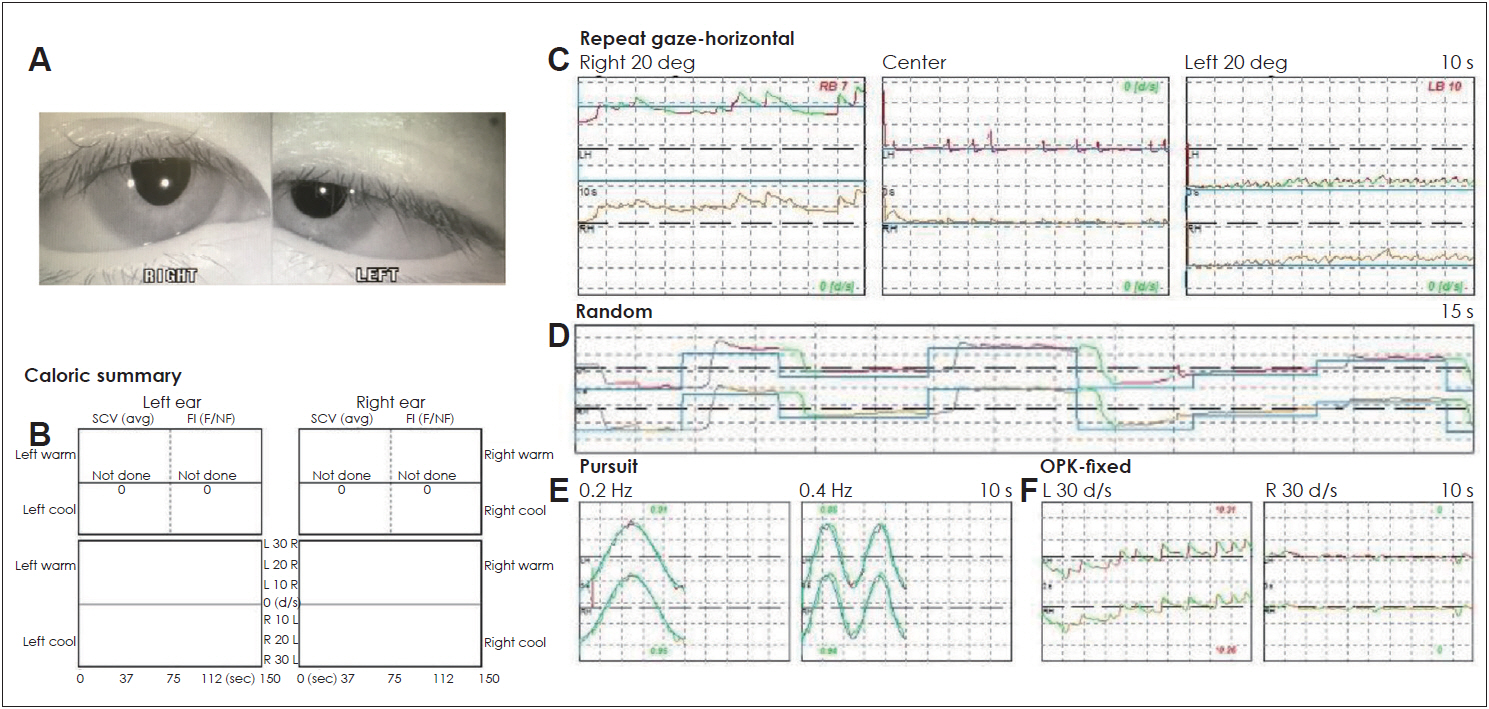

Initial evaluation for the nystagmus. (A) Right six cranial nerve palsy when the patient looked to the right side. (B) No response in caloric test due to vestibular suppressant medication. (C) Gaze-induced nystagmus (right beating nystagmus looking to right side and left beating nystagmus looking to left side). (D) Normal saccade test. (E) Normal pursuit test. (F) Abnormal optokinetic eye movement in both directions. L: left, R: right, deg: degree, s: second, Hz: Hertz.

Several neurological examinations were performed to identify the underlying causes, but the tests were negative for the following (Fig. 2): thymus and acetylcholine receptor antibody test for myasthenia gravis, bone marrow testing for acute leukemia, normal homocysteine, and serology for the EpsteinBarr virus.

Patient’s laboratory results. (A) Megaloblastic anemia in peripheral blood smear (×400). (B, C) Normal configuration of cells in bone marrow (× 400 and × 1,000). (D) Results in laboratory tests including normal values. WBC: white blood cell, Hb: hemoglobin, Plt: platelet, TIBC: total iron binding capacity, ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate, PT: prothrombin time, PTT: partial thromboplastin time, EBV: Epstein-Barr virus, IgM: immunoglobulin M, AchR Ab: acetylcholine receptor antibody.

Temporal MRI with angiography, with constructive interference in steady state, demonstrated a right vertebral artery stenosis (Fig. 3A and B) with basal ganglia hyperintensity (Fig. 3C). Although there was insufficient evidence for VBI by MRI, the patient had received a blood transfusion of 5.0 units of hemoglobin due to excessive menstrual bleeding a month before and recent medication for hypertension, which would cause inadequate blood circulation to the brainstem.

Microvascular ischemia in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with angiography. (A) Right vertebral stenosis (white arrow) in magnetic resonance angiography. (B) Stenosis of right vertebral artery (black arrow) in T2W MRI. (C) Hyperintensity (white arrows) in both basal ganglia. L: left, R: right.

For treatment, dimenhydrinate at 40 mg/day, diazepam at 4 mg/day orally, and 25 mg of intravenous metoclopramide were administered with conservative management. On day 7, she was free of diplopia in all gaze positions (Fig. 4). Gait disturbances recovered more slowly. She had normal results in the caloric test and other nystagmus tests. Two days of skipping medication recovered the caloric response. The initial abnormal gaze reduced and optokinetic nystagmus resolved to normal. Follow-up for 2 months after discharge showed no abnormality of eye movement in the patient, and iron supplements and hypertension medications were maintained.

Discussion

VBI is a condition characterized by poor blood flow to the posterior portion of the brain, such as the cerebellum or brainstem [6], which is fed by two vertebral arteries that combine to form the basilar artery. It is presented with symptom of vertigo, combined with visual symptoms such as diplopia, field defects, hallucinations, headache, hearing loss, and incorporation [7]. Transient ischemic attacks due to VBI have, by definition, symptoms resolved within 24 hours [8]. To diagnose VBI, imaging studies such as MRI with angiography are needed for detecting ischemic changes in the vertebrobasilar distribution [9]. However, they can often overestimate the degree of stenosis, or misrepresent stenosis as an occlusion. In our case, the patient presented with right sixth cranial nerve palsy in the right eye and signs of central vertigo with gaze-induced nystagmus in both sides and spontaneous upbeating nystagmus. We suspected the possibility of a lesion in the brainstem including the pons, but the initial imaging evaluation did not reveal any evidence of infarction or hemorrhage in the brainstem. MRI with angiography showed right vertebral artery stenosis and hyperintensity on basal ganglia. Although the stenosis of unilateral vertebral artery in MRI was not adequate evidence, the severe megaloblastic anemia, recurrent vertigo, and fast recovery could support the diagnosis of sixth cranial nerve palsy with vertigo due to VBI. The patient showed elevated serum cobalamin (vitamin B12), a clinical sign indicating functional and qualitative vitamin B12 deficiency [10].

Sixth cranial nerve palsy is a common neuro-ophthalmic disorder often presenting to the general ophthalmologist [11]. Various etiologies have been identified, such as, congenital abnormalities, trauma, inflammation, and autoimmune disease. Microvascular ischemia is the most common cause of sixth cranial nerve palsy in adults without any history of trauma or congenital brain malformations. As many as 50% of sixth cranial nerve palsies are attributable to IMN, often found in patients with diabetes mellitus or arterial hypertension [12]. The most common risk factors for microvascular ischemic sixth nerve palsy include hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, and alternative signs of hypertensive end-organ damage such as left ventricular hypertrophy. We suspected that our patient had risk factors for ischemic changes in the brainstem. The hyperintensity in the basal ganglia, especially the globus pallidus, on T1-weighted MRI suggests that the lesions represent incomplete ischemic injury like hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy or acute cerebral infarction [13]. Abducens palsy is rarely a sign of acute myeloid leukemia [14]. The presentation of myasthenia gravis in an isolated sixth cranial nerve palsy has been reported [1]. Infectious mononucleosis can precede isolated abducens nerve palsy, as an association between hyperhomocysteinemia and isolated abducens nerve palsy is known [15,16]. To exclude these causes related to anemia in our patient, we performed several tests, which showed negative results.

In this case, our patient presented with an isolated sixth cranial nerve palsy with central vertigo and gaze-induced nystagmus, but with no acute hemorrhage or infarction on CT and MRI images. Clinicians receiving such a consultation from a neurology department for evaluating peripheral vertigo should consider the possibility of VBI if the patient has high risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, anemia and volume depletion which can cause insufficient circulation.

Supplementary Material

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at (https://doi.org/10.7874/jao.2019.00311).

Supplementary Video

Video 1. Initial video nystagmography in patient with gaze disturbance of right abduction and gaze induced nystagmus.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (NRF-2019K 1A3A1A47000527).

Notes

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Seung Won Paik. Data curation: Seung Won Paik and Hui Joon Yang. Writing—original draft: Young Joon Seo. Writing—review & editing: Seung Won Paik.