|

|

- Search

| J Audiol Otol > Volume 27(2); 2023 > Article |

|

Abstract

Cochlear implants (CIs) restore hearing in patients with severe-to-profound deafness. Post-CI meningitis is a rare but redoubted complication. We present the case of a five-year-old CI recipient who experienced an episode of chronic meningitis caused by chronic otitis media with cholesteatoma encasing the electrode lead. We hypothesize that the cholesteatoma led to an ascending infection to the cochlea, passing through the labyrinths, resulting in chronic meningitis. Although positive neural responses were initially noted on cochlear electrical stimulation, these responses resolved a few weeks after reimplantation. Our report highlights the importance of careful otoscopic examination and diagnostic work-up in patients presenting with otogenic meningitis to rule out cholesteatoma formation and to ensure prompt surgical exploration if warranted.

Cochlear implants (CIs) are hearing devices commonly used to treat the severely hard of hearing and profound deaf worldwide. By electrically stimulating the inner ear, it produces hearing sensations [1]. Post-CI meningitis is rare but a wellknown risk especially in those with an abnormal cochlear anatomy [1,2]. Despite efforts such as vaccination and product improvements, a post-implantation acute meningitis incidence of 0.2% remains [3]. We present an unusual case of chronic meningitis in a child with a CI.

A 5-year-old boy presented to our clinic with persistent episodes of meningitis for 3 months. His medical history contained bilateral CI placement (Cochlear Nucleus® 24RE [CA]) at 9 months of age because of congenital sensorineural hearing loss with a normal middle and inner ear anatomy on radiological imaging. Genetic testing revealed a GBJ2 mutation as a causative factor for his hearing loss. One year after implantation, his right CI was explanted because of implant infection, followed by successful reimplantation after 3 months with normal language and speech development during early childhood. There was no medical history of frequent infections or immune diseases and he was fully vaccinated.

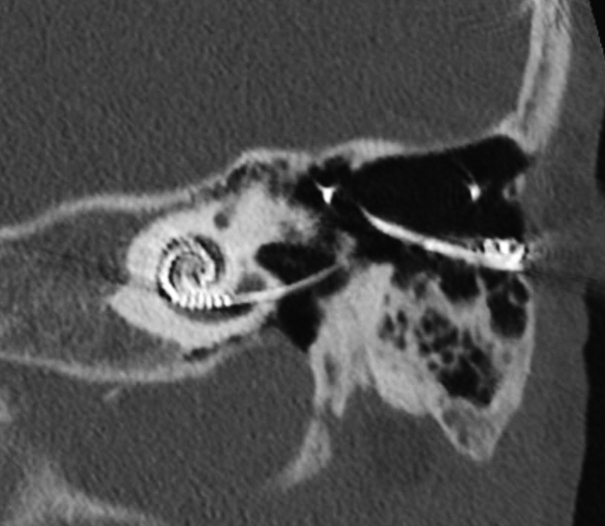

The disease episode was preceded by short periods of recurrent otorrhea on the left side for which topical antibiotics were given (framycetin, gramicidin, dexamethasone solution). Subsequently, he developed an acute left peripheral facial nerve palsy that resolved after prednisone treatment. Two weeks later he was hospitalized because of headache, fever, and malaise. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) obtained by lumbar puncture showed pleocytosis, suggesting bacterial meningitis. Hematological and CSF samples repeatedly tested negative for bacterial and viral agents. Otoscopic examination was performed, demonstrating an intact eardrum and aerated middle ear. Additional computed tomography (CT) scan was performed, with findings of opacification of the mastoid air cells (Fig. 1). Despite intravenous treatment with various antibiotics (amoxicillin, ceftriaxone, vancomycin) and partial resolution of opacification on sequential CT scan, the meningitis persisted. A positron emission tomography (PET) scan to identify additional sources of inflammation revealed high tonsillar metabolic activity, whereafter a tonsillectomy was performed. Histopathological examination showed no signs of tonsillar lymphoma or chronic inflammation and no effects were observed on the meningitis. The patient was then referred for a second opinion to our tertiary clinic, three months after the initial presentation.

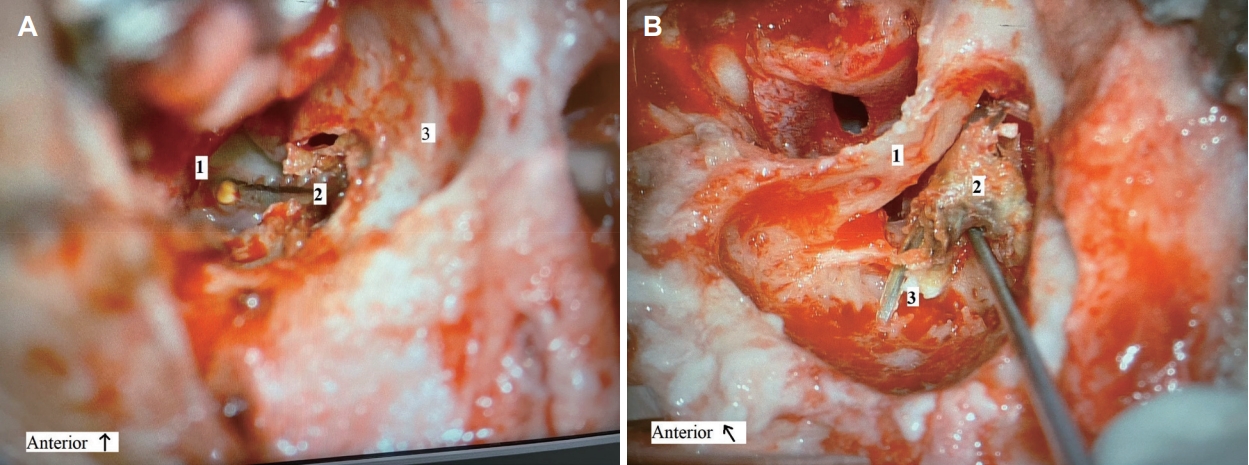

Here, a small bony defect superior and lateral to the bony annulus was observed upon otoscopic examination of the left outer ear canal. This was covered by squamous epithelium in which a part of the electrode lead was visible. An aerated middle ear with intact tympanic membrane was seen, without signs of acute inflammation such as ear discharge. The left CI was functioning normally subjectively. Based on the suspicion of cholesteatoma formation affecting the electrode lead, cochlear explantation was proposed. During the mastoidectomy, local cholesteatoma formation was observed originating from the bony defect in the outer ear canal and extending in the facial recess in which matrix was wrapped around the electrode lead (Fig. 2). Otherwise, the middle ear was free of pathology and there were no signs of local inflammation or other bony erosions in the mastoid or middle ear. The cholesteatoma was removed and the bony defect of the ear canal was closed with cartilage. Upon removal of the electrode from the cochleostomy, pus discharged out of the cochlea into the middle ear. After cessation of active discharge, and by the lack of other visual abnormalities seen through the cochleostomy, a dummy contour advance electrode was placed to facilitate future reimplantation.

Within 12 hours after surgery, symptoms of fever and meningitis disappeared. Bacterial culture of the cochlear discharge showed an Achromobacter xylosoxidans infection. Therefore, the patient was treated with ceftazidime for 1 week and cotrimoxazole until reimplantation surgery, without any further recurrence of meningitis.

A reimplantation was timed 4 months after explantation, as recommended by previous studies to achieve histopathological clearance of the infection [4]. During this surgical procedure, a small residual cholesteatoma pearl was removed in the area of the previous bony ear canal defect. Upon removal of the dummy electrode out of the cochlea, which was stuck in the depth of the cochlear turns, the sheet of the dummy electrode was torn off. A part of the basal turn was drilled out in an attempt to reach the residual part of the electrode. However, the dummy could not be fully removed, leaving a part of the sheet inside. After testing the patency of the cochlea with a depth gauge, a new cochlear electrode (Cochlear Nucleus® CI612 [CA]) was fully inserted. Perioperative measures were performed: impedances were within normal limits (between 7.6 kΩ and 19.7 kΩ in common ground modus) and electrically evoked compound action potentials (eCAPs) were obtained across the array. The measurements were obtained via the auto neural response telemetry (NRT) algorithm from Cochlear Ltd. [5]. Thresholds for the eCAP growth curve (t-NRT) were determined by the software and later manually checked by an experienced audiologist (HH). Neural response could be measured at 11 electrodes (21, 20, 17, 15, 14, 10, 9, 8, 6, 5, and 4). A postoperative CT showed correct positioning of the CI into the cochlea, passing the remnant of the dummy electrode in the basal and second turn of the cochlea (Fig. 3).

One month after reimplantation the CI was activated but no hearing response could be elicited. In subsequent visits during the next weeks neither hearing responses at higher levels of stimulation, nor eCAPs could be obtained. The clinical specialist from the manufacturer was consulted and the case was discussed. First, it was verified that the per-operative eCAPs were present. Second, an extensive fitting session was conducted in which only stimulation at electrode 20 and at very high pulse widths and high current levels could elicit a repeatable response ‘loud.’ There were no responses at lower levels or at other electrodes. Third, an integrity test was performed by the manufacturer. It showed that the receiver-stimulator and electrode were operating normally, and that the CI was classified as a functioning device [6]. A second CT confirmed the stable electrode position. Hypothetically, the late consequences of the previous chronic meningitis and concomitant labyrinthitis were disastrous for the remaining nervous tissue of the cochlea. Although eCAPs could be elicited during surgery, they disappeared in the period after reimplantation. Revision surgery was discussed. However, this was not considered to result in reasonable hearing outcomes with a CI. Alternatives such as auditory brainstem implants were discussed with the parents of the child as a last resort.

We presented an exceptional case of a boy with a CI complicated by chronic bacterial meningitis after an episode of chronic otitis media (OM) with cholesteatoma formation. Potentially, biofilm formation of the electrode lead at the side of the cholesteatoma formation resulted in an ascending infection into the cochlea, leading to labyrinthitis and chronic meningitis. Interestingly, treatment delay of the meningitis occurred by the lack of otoscopic anomalies during initial presentation with meningitis, partial resolution of previous opacification of the mastoid on sequential CT imaging, and a negative PET-CT during diagnostic work-up. It was only upon discovery of the bony defect in the outer ear canal, in combination with remaining opacification on CT, that the chronic meningitis was explained. This finally resulted in immediate removal of the CI, with cessation of meningitis symptoms.

In literature, hematogenous and otogenic routes are described to explain otitis related meningitis. Otogenic distribution of pathogens out of the middle ear to the brain can spread directly via a defect in the tegmen tympani, or indirectly via the inner ear [7,8]. An animal study by Wei, et al. [9] showed that the bacterial load needed to cause meningitis was reduced in rats with a CI in situ compared to those without a CI. This was true for all infectious routes, both the hematogenous and otogenic [9]. Therefore authors suggested that the presence of a CI, possibly through a foreign-body reaction, could predispose a recipient to meningitis [7,8].

When the CI was introduced, post-CI bacterial meningitis was assumably uncommon until a sudden incidence peaked in 2002 [2,3]. This leads to international investigation of all previous CI-recipients to find causative factors, leading to abandoning of a two-part electrode design [3,10]. However, meningitis after CI is still a concern, especially in patients with risk factors such as young age, an immunocompromised status, and cochlear malformation [2]. Minimizing traumatic electrode insertion, sealing of the cochleostomy site (especially in patients with cochlear anomalies), and adequate immunization are all considered to reduce the chance of meningitis [1,11,12].

In current practice guidelines, it is stated that CI recipients with an acute OM are advised to seek medical care and to be treated with antibiotics immediately after diagnosis to reduce the chance of meningitis [11]. The presence of a cholesteatoma makes the ear prone to recurrent bacterial infection and biofilm formation around the lead, thereby causing otogenic dissemination and meningitis. Magnetic resonance/diffusion-weighted imaging can be used to diagnose cholesteatoma; however, the use is limited in CI recipients. Therefore, careful otoscopic examination is particularly important in OM patients with a CI to rule out any visual defects from the outer ear canal or tympanic membrane as a sign of potential cholesteatoma formation.

As we demonstrated, meningitis can still occur despite an optimized CI design, adjusted surgical techniques and adequate vaccination. The child in our case was fully vaccinated, had a normal immunologic status, and did not suffer from meningitis-related syndromes. It is remarkable that the contralateral CI was also explanted at a younger age due to an infection. No relation could be found between both events.

The electrode implantation itself is a traumatic event, possibly leading to inflammatory reactions and direct or delayed damage to the cochlea and sensory elements [4]. Besides this, the deleterious effects could be a result of labyrinthitis in a CI-implanted child. To be noted, the pathogenesis of a labyrinthitis involves different stages whereby an acute inflammation can progress to stages characterized by fibrosis and even ossification. Previously, it has been demonstrated that a suppurative labyrinthitis can even result in necrosis of the membranous labyrinth [13]. Moreover, cytotoxic effects during a labyrinthitis may be lethal to the sensory structures of the inner ear with loss of auditory function [13]. Previous temporal bone studies in meningogenic labyrinthitis cases have demonstrated loss of spiral ganglion cells, inner and outer hair cells, and damaging effects to the peripheral auditory axons, aside from fibrosis and ossification [14]. This all could be the reason why initially the eCAP response was present, but disappeared in later stages [13]. This once again underlines the need for immediate action of health care providers to promptly act in case of any potential sign of OM, or even advanced stages such a labyrinthitis or meningitis in CI recipients.

In conclusion, our rare case of chronic bacterial meningitis in a CI-patient is a lesson for all clinicians and underlines the importance of careful otoscopic examination, diagnostic work-up, and consideration of surgical exploration to rule out and evacuate cholesteatoma formation as a source for meningitis and promptly act on OM in such cases. Moreover, in this case, we discussed the potentially deleterious effects of chronic meningitis and labyrinthitis to the peripheral auditory elements limiting CI performance.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery and the Brain Center of University Medical Center Utrecht (Utrecht, The Netherlands). Authors thank Cochlear Ltd. for technical support on this case.

Notes

Ethical Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the parents. All procedures involving human subjects were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the University Medical Center Utrecht (Utrecht, The Netherlands) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: all authors. Data curation: all authors. Formal analysis: all authors. Investigation: Hiske W. Helleman, Adriana L. Smit. Supervision: Hiske W. Helleman, Adriana L. Smit. Validation: all authors. Visualization: Hanneke D. van Oorschot, Adriana L. Smit. Writing—original draft: all authors. Writing—review & editing: all authors. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography scan of the left mastoid indicating opacification of the mastoid air cells around the electrode lead. A: Axial view. B: Coronal view.

Fig. 2.

Perioperative image of local cholesteatoma formation originating from the bony defect in the outer ear canal and extending in the facial recess in which matrix was wrapped around the electrode lead. A: Middle ear with bony defect of the outer ear canal due to cholesteatoma. A patch of fibrosis sealing the cochleostomy site before the electrode was removed and pus discharged out of the cochlea. 1, cochleostomy; 2, electrode lead; 3, posterior wall of ear canal. B: Cholesteatoma matrix out of the facial recess wrapped around the electrode lead, extending into the mastoid. 1, posterior wall of ear canal; 2, cholesteatoma sac; 3, electrode lead.

REFERENCES

1. Rubin LG, Papsin B. Cochlear implants in children: surgical site infections and prevention and treatment of acute otitis media and meningitis. Pediatrics 2010;126:381–91.

2. Lalwani AK, Cohen NL. Does meningitis after cochlear implantation remain a concern in 2011? Otol Neurotol 2012;33:93–5.

3. Terry B, Kelt RE, Jeyakumar A. Delayed complications after cochlear implantation. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015;141:1012–7.

4. Manrique-Huarte R, Huarte A, Manrique MJ. Surgical findings and auditory performance after cochlear implant revision surgery. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2016;273:621–9.

5. van Dijk B, Botros AM, Battmer RD, Begall K, Dillier N, Hey M, et al. Clinical results of AutoNRT, a completely automatic ECAP recording system for cochlear implants. Ear Hear 2007;28:558–70.

6. Battmer RD, Backous DD, Balkany TJ, Briggs RJ, Gantz BJ, van Hasselt A, et al. International classification of reliability for implanted cochlear implant receiver stimulators. Otol Neurotol 2010;31:1190–3.

7. Wei BP, Robins-Browne RM, Shepherd RK, Clark GM, O’Leary SJ. Can we prevent cochlear implant recipients from developing pneumococcal meningitis? Clin Infect Dis 2008;46:e1–7.

8. Wei BP, Shepherd RK, Robins-Browne RM, Clark GM, O'Leary SJ. Pneumococcal meningitis post-cochlear implantation: potential routes of infection and pathophysiology. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010;143(5 Suppl 3):S15–23.

9. Wei BP, Shepherd RK, Robins-Browne RM, Clark GM, O’Leary SJ. Threshold shift: effects of cochlear implantation on the risk of pneumococcal meningitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007;136:589–96.

10. Lalwani AK, Cohen NL. Longitudinal risk of meningitis after cochlear implantation associated with the use of the positioner. Otol Neurotol 2011;32:1082–5.

11. Gluth MB, Singh R, Atlas MD. Prevention and management of cochlear implant infections. Cochlear Implants Int 2011;12:223–7.

12. Wei BP, Shepherd RK, Robins-Browne RM, Clark GM, O’Leary SJ. Pneumococcal meningitis post-cochlear implantation: preventative measures. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010;143(5 Suppl 3):S9–14.

13. Schuknecht HF. Pathology of the ear. Cambridge: Harvard University Press;1974.