|

|

- Search

| J Audiol Otol > Volume 22(3); 2018 > Article |

|

Abstract

Background and Objectives

Patulous Eustachian tube (PET) causes troublesome autophony. We treated PET using tragal cartilage chip insertion to fill in the concavity within the tubal valve and evaluated the feasibility of this method.

Subjects and Methods

This study used a prospective design. Eleven patients with PET disorder were included. Tragal cartilage chip insertion via a transcanal approach into the Eustachian tube (ET) was performed in 14 ears of those patients. They were followed-up for at least 12 months after surgery and were evaluated by symptom questionnaire scores.

Results

The average follow-up was 16.4 months. Thirteen of fourteen ears received immediate complete relief of autophony symptoms. Autophony symptoms at the last follow-up were as follows: four ears (28.6%) had complete relief; five ears (35.7%) showed satisfactory improvement; four ears (28.6%) showed significant but unsatisfactory improvement; and one ear (7.1%) was unchanged. The PET symptom questionnaire in the affected ears showed a significant reduction in autophony (p=0.047) and improvement in breathing sound conduction (p=0.047). There were no complications such as otitis media or occlusion symptom.

Patulous Eustachian tube (PET) is a pathologic state characterized by symptoms of aural fullness, autophony, and the hearing of physiologic breathing sounds, which was first described in the late 1800s by Schwartze [1] and Jago [2]. The Eustachian tube (ET) links the middle ear to the nasopharynx, which is usually closed at rest and transiently opens during normal swallowing. However, abnormal persistent opening of the valve at rest leads to symptoms of PET [3].

Most cases subside spontaneously, but there are some intractable cases that require surgical procedures. Surgical treatments can be classified into three categories: 1) narrowing of the lumen of the ET by injecting a bulky agent, 2) surgical ligation of the ET orifice, and 3) plugging of the lumen with various materials [4].

Surgical treatments are ultimately undertaken to obstruct the ET lumen. Trials to obstruct the ET lumen have been conducted by various means, such an indwelling catheter [5], a silicone plug [6], and cartilage block [7], in addition to injecting small pieces of cartilage [8]. We modified the tragal cartilage plugging method, which was first reported by Kobayashi [7]. Our method can eliminate the risk of foreign body, while being considered more physiologic as it can reduce damage to Eustachian valve. Here, we evaluated the feasibility of modified tragal cartilage chip insertion technique via transcanal approach for treatment of PET.

This study used a prospective design. We included 14 ears from 11 patients who were diagnosed with PET under previously established diagnostic criteria (Table 1) [9]. All the patients were intractable to conservative therapy or ventilation tube insertion for more than one year.

Pure tone audiometry, a PET symptom questionnaire survey which was rated on a scale of zero to ten, and autophony symptom score (Table 2) [9] were evaluated preoperatively, at 1 month after surgery (immediate follow-up), and during last follow-up visit (>12 months). The Institutional Review Board of the authorsŌĆÖ institution approved this study (IRB No. 4-2017-1184). Informed consent was obtained from each subject.

Preoperative and postoperative hearing thresholds were analyzed by nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test, while PET symptom questionnaires before surgery, at immediate followup, and at last follow-up were analyzed with nonparametric Friedman test using IBM SPSS 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

All surgeries were performed under local anesthesia. All surgeries were performed using microscope, except for the last one case, which used endoscope. Since endoscopic approach offered clearer and more magnified view of ET orifice compared to microscopic approach, it was thought to be more suitable than microscopic approach for manipulating ET. However, due to the lack of experience with endoscopic ear surgery, microscopic approaches were performed in the early period. The patient was placed in the supine position, and the head was rotated to the opposite side. The ear was prepared and draped in a sterile fashion. Injection with 1% xylocaine and 1:100,000 epinephrine was administered into the external auditory canal. Myringotomy was performed at the anteriosuperior aspect of the tympanic membrane. After myringotomy, ET was identified and probed. Bleeding was controlled with cotton soaked in epinephrine.

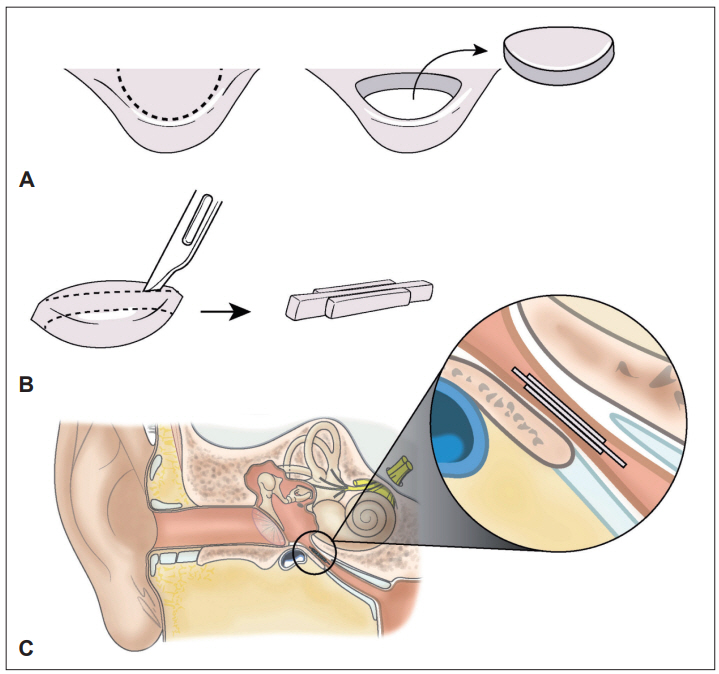

Tragal cartilage was then harvested in the largest possible quantity, preserving a width of 2-3 mm in the cartilage rim to maintain the shape of the cartilage. From the harvested cartilage, a long and thin piece of cartilage (up to 15 mm) was cut diagonally in order to make it as long as possible, and two smaller ones (7-8 mm) were also created. There might be small variations in length and shape according to patients, as the ET structure slightly differs among patients. Perichondrium was also harvested. Tragal cartilages were inserted into ET orifice through myringotomy site. First, the longest piece of cartilage was inserted and reached the isthmus to obstruct it partially. Next, the smaller pieces were inserted on both sides of the longest to obstruct ET, as well as for reinforcement. The inserted pieces of cartilage were reinforced with perichondrium, if necessary. Finally, a paper patch was applied to myringotomy site (Fig. 1, Supplementary Video 1 in the onlineonly Data Supplement).

Fourteen ears of eleven patients were included in this study. The average age of the patients was 40.8 years, and there were two males and nine females. The average observation period was 16.4 months, and no complications were observed. The preoperative and postoperative average pure tone audiometry did not show a statistically significant difference, at 20.5 dB and 21.1 dB, respectively (p=0.761). The chief preoperative complaint was voice echoing, followed by breathing sounds and a sense of ŌĆ£shiveringŌĆØ in the tympanic membrane. There were no complications such as otitis media or occlusion symptoms (Table 3).

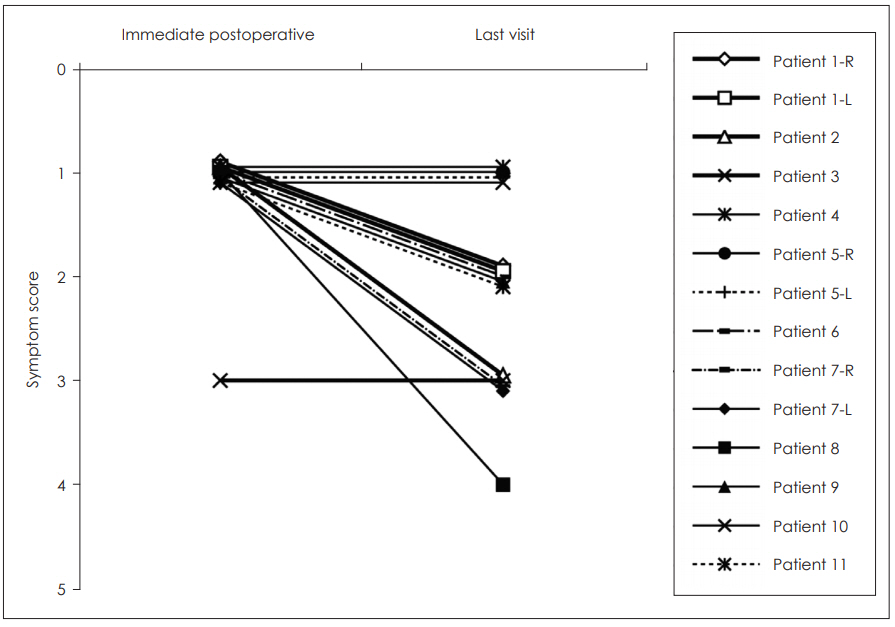

In the PET symptom questionnaire, voice echoing which is associated with autophony and breathing sounds were improved (Fig. 2).

The optimal treatment for PET has not been established clearly, and depends on the severity of the symptoms [6]. Conservative methods are usually recommended, such as sufficient hydration, weight gain, saline nasal irrigation, and reassurance [4]. Some medications, including anxiolytics, Chinese herbal medicines, sympathomimetic agents [6], nasal steroid sprays, estrogen nasal solution, and topical irritants to induce mucosal edema [4], are helpful.

However, surgical methods are required in some intractable and persistent cases. Physiologically, closure of the ET is maintained by the mucosal valve of the cartilaginous portion, which is approximately 5 mm in length and is located about 10 mm distal to the tube from the torus tubarius [3]. Different surgical trials have been conducted aiming to narrow the lumen of ET, with varying success rates (Table 5) [5,10-17].

Previously, Kobayashi [7] tried to treat PET using the transtympanic cartilage insertion method. However, they changed the plugging material to tailored silicon tube. The average length of ET from middle ear orifice to nasopharyngeal orifice was about 35 mm, and its isthmus was about 12 mm distance from middle ear orifice. Therefore, they thought it was difficult to completely obstruct or probe the valve portion of ET. Thus, they designed a 22- to 25-mm-long silicon tube and reported good results [6]. After modifying the shape of this silicon tube, they recently reported that success rate of these old and new type silicon tubes for PET was 83.0%, based on evaluation of 252 ears from 191 patients [18]. Despite these favorable results, there are still some limitations in this silicon tube insertion technique: first, it may cause a foreign body reaction in the tissue; second, normal bony portion of ET and the narrow isthmus structure could be injured when the silicon tube passes through them; and lastly, otitis media with effusion may occur if ET is obstructed completely with a silicon tube.

If we can use cartilage chip more efficiently and firmly, we can achieve more favorable results while reducing the risk of foreign body reaction, maintaining physiologic function such as middle ear gas exchange and clearing of middle ear secretions, and preventing the possibility of middle ear effusion or otitis media.

Our modified transtympanic cartilage insertion technique is different from the original technique used by Kobayashi [7]. We used longer cartilage chip which can reach ET isthmus, even though it cannot pass through the isthmus. We also used two more cartilage chips and perichondrium to reinforce the first cartilage chip, and to reduce the recurrence of symptoms resulting from tissue absorption.

Although our technique neither crosses the isthmus nor completely closes the valve, it can sufficiently obstruct the isthmus. More than 92% of examined ears showed complete symptom relief immediately, and this was the evidence of sufficient obstruction. Cartilage can reach and obstruct the isthmus (Fig. 1). During more than 12 months of follow-up, two-thirds of the patients maintained their improvement, and this was similar to the results from other previous reports, some of which used silicone tubes (Table 5). We performed revision surgery, of which the result was not included in this study, in one patient who had no improvement in symptoms after eight months since first surgery, and found that the previously inserted cartilage was not absorbed. In this respect, it is supposed that the absorption is slight and the effect of insertion persists for a long time.

This type of insertion has some benefits compared with silicon tube insertion that crosses the isthmus. First, this procedure does not involve complete passage through the valve, so it can reduce the risk of injury to structures surrounding the valve and possible complications. Despite the lack of complete passage through the valve, the symptoms were improved significantly. Second, autologous tragal cartilage is used to reduce the risk of a foreign body reaction compared with the method that uses a foreign silicon tube. Third, the risk of otitis media resulting from complete closure in other previously reported methods is reduced. Fourth, our technique is easier than other previously reported methods. It is not necessary for the insertion to be deep enough to pass completely through the valve. Also, tympanomeatal flap elevation and myringoplasty need not be performed to facilitate the handling of inserted material. Finally, the use of autologous cartilage requires no additional approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), as well as no additional cost for buying the material.

At the last follow-up visit in some patients, postoperative autophony symptom scores were slightly higher than those at the immediate follow-up visit. These patients with recurred symptoms had surgery in early period. During early period, we did not obstruct the isthmus completely to reduce the risk of otitis media, and we believe this gap could have induced absorption of inserted cartilage and recurrence of symptoms. However, we later inserted cartilage to completely obstruct the isthmus, considering slight absorption of cartilage with passage of time.

Nevertheless, voice echoing, which is associated with autophony, was improved significantly at the immediate and final follow-up visits. Based on these results, we determined that some symptoms that are related to autophony seem to re-appear, although the severity of the symptoms seems to be improved.

In our method, once myringotomy and ET orifice probing is performed, only the trimmed cartilage needs to be inserted into the orifice, which is then obstructed with perichondrium. Due to the ease of handling, the estimated time of surgery is shortŌĆöapproximately 30 minutesŌĆöand the surgery can be completed under local anesthesia.

In conclusion, transtympanic cartilage chip insertion into the ET via the transcanal anterior superior myringotomy technique represents a safe and accessible surgical option for the treatment of PET and provides a reliable and satisfactory outcome for PET patients.

Supplementary Material

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at (https://doi.org/10.7874/jao.2018.00017).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant of the Yonsei University College of Medicine (6-2016-0084).

The authors would like to thank Dong-Su Jang, MFA (Medical Illustrator, Medical Research Support Section, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea) for his help with the illustrations.

Fig.┬Ā1.

A: Autologous tragal cartilage was harvested, preserving a width of 2-3 mm in the cartilage rim. B: A long and thin piece of cartilage (15 mm) was cut diagonally in order to make it as long as possible, and two smaller ones (7-8 mm) were also created. C: The three cartilage pieces were inserted through the myringotomy site. First, the longest piece was inserted and reached the isthmus to obstruct it partially. Next, the smaller pieces were inserted on both sides of the longest to reinforce it.

Fig.┬Ā2.

Postoperative PET symptom questionnaire; voice echoing which is associated with autophony and breathing sounds were improved significantly, but aural fullness and hyperacusis were not. PET: patulous Eustachian tube.

Fig.┬Ā3.

Postoperative autophony symptom score at the immediate postoperative period and last visit; symptoms disappeared in most of the patients at the immediate postoperative period; however, over time, the symptoms re-appeared in some patients.

Table┬Ā1.

PET diagnostic criteria

Table┬Ā2.

Patient telephone PET questionnaire and autophony symptom score

Table┬Ā3.

Patient demographics

Table┬Ā4.

Postoperative autophony symptom score

Table┬Ā5.

Methods used to treat patulous Eustachian tube

| Study | Method | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Pulec [10] | Polytetrafluoroethylene (Teflon) paste injection anterior to ET orifice | Symptom improvement in 73% (19/26) of patients |

| Stroud, et al. [11] | Replacement of tensor veli palatini muscle | Symptom improvement in 90% (9/10) of patients |

| Bluestone and Cantekin [5] | ET and ventilator tube insertion | Symptom improvement in four patients |

| Chen and Luxford [12] | Ventilator tube insertion | Effective in 70% (9/13) of patients |

| Endo, et al. [13] | Effective in 90.9% (10/11) of patients | |

| Doherty and Slattery [14] | Autologous fat graft via the intranasal approach | Symptom improvement in two patients |

| Takano, et al. [15] | Closure of the nasopharyngeal aspect of the ET | Symptom improvement in 60% (6/10) of patients |

| Kong, et al. [16] and Oh, et al. [17] | Calcium hydroxyapatite injection | Symptom improvement in three patients |

REFERENCES

1. Schwartze H. Respiratorische bewegung des trommelfelles. Arch Ohrenheilkd 1864;1:139

3. Poe DS. Diagnosis and management of the patulous eustachian tube. Otol Neurotol 2007;28:668ŌĆō77.

4. Grimmer JF, Poe DS. Update on eustachian tube dysfunction and the patulous eustachian tube. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005;13:277ŌĆō82.

5. Bluestone CD, Cantekin EI. ŌĆ£How I do itŌĆØ--otology and neurotology. A specific issue and its solution. Management of the patulous Eustachian tube. Laryngoscope 1981;91:149ŌĆō52.

6. Sato T, Kawase T, Yano H, Suetake M, Kobayashi T. Trans-tympanic silicone plug insertion for chronic patulous Eustachian tube. Acta Otolaryngol 2005;125:1158ŌĆō63.

7. Kobayashi T. Diagnosis and treatment of patulous eustachian tube. Pract Otol (Kyoto) 2000;93:897ŌĆō907.

8. Oh SJ, Lee IW, Goh EK, Kong SK. Endoscopic autologous cartilage injection for the patulous eustachian tube. Am J Otolaryngol 2016;37:78ŌĆō82.

9. Brace MD, Horwich P, Kirkpatrick D, Bance M. Tympanic membrane manipulation to treat symptoms of patulous eustachian tube. Otol Neurotol 2014;35:1201ŌĆō6.

10. Pulec JL. Abnormally patent eustachian tubes: treatment with injection of polytetrafluoroethylene (Teflon) paste. Laryngoscope 1967;77:1543ŌĆō54.

11. Stroud MH, Spector GJ, Maisel RH. Patulous eustachian tube syndrome. Preliminary report of the use of the tensor veli palatini transposition procedure. Arch Otolaryngol 1974;99:419ŌĆō21.

12. Chen DA, Luxford WM. Myringotomy and tube for relief of patulous eustachian tube symptoms. Am J Otol 1990;11:272ŌĆō3.

13. Endo S, Mizuta K, Takahashi G, Nakanishi H, Yamatodani T, Misawa K, et al. The effect of ventilation tube insertion or trans-tympanic silicone plug insertion on a patulous Eustachian tube. Acta Otolaryngol 2016;136:551ŌĆō5.

14. Doherty JK, Slattery WH 3rd. Autologous fat grafting for the refractory patulous eustachian tube. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003;128:88ŌĆō91.

15. Takano A, Takahashi H, Hatachi K, Yoshida H, Kaieda S, Adachi T, et al. Ligation of eustachian tube for intractable patulous eustachian tube: a preliminary report. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2007;264:353ŌĆō7.

16. Kong SK, Lee IW, Goh EK, Park SH. Autologous cartilage injection for the patulous eustachian tube. Am J Otolaryngol 2011;32:346ŌĆō8.